Forgive, please, the late, overhasty and not especially informative nature of this post, but I wished to get something up for Earth Day before the opportunity passed. As usual, consider yourself invited to report on your own Earth Day activities in the comments section.

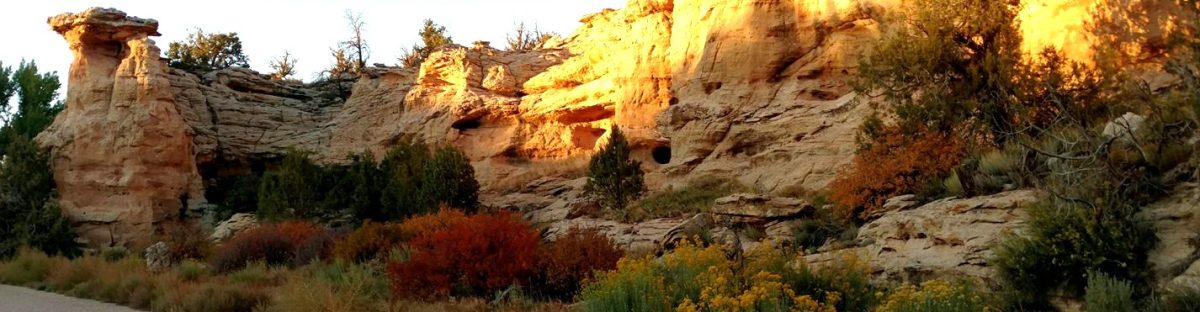

Here in SE Utah, Earth Day opened gorgeously. Warm and blue. To the south, only a few drawn clouds showing, thin as weeds that snow flattened. Around the Abajos to the north rise those striking cloud formations that always provoke my wonder. Can’t remember what they’re called, but I think of them as the “jellyfish formations,” because to my eye they resemble man-of-war jellyfish: small, top-heavy clouds trailing long, wispy tentacles of vapor that appear to dangle into lower reaches of the atmosphere. As I’ve sought to understand those cloud structures, I’ve read what’s actually happening is that the tentacles are water vapor rising out of unstable air, seeking a more settled region of the atmosphere. Once the vapor finds that more stable region it forms a cumulus cloud, which may in turn provide the seed of a cumulonimbus cloud, a thunderhead.

To start my Earth Day in what’s becoming my customary fashion, I’ve gone alone to my favorite high perch in Crossfire’s cliffs to be with the birds. Coincidently, the first winged visitors to arrive are— heh— turkey vultures, four of them. I’m looking in the opposite direction from which they approach, so the first clue I have of their presence is the rustling of large wings.

Maybe people aren’t aware of how much noise birds make when they fly. In the past, I’ve felt clumsy in the desert and as if the noise I made in passing was somehow unnatural and intrusive. After four years of learning to, first, go more quietly myself, and second, hear the wild mixture of presences, from wings ruffling the air to lizard feet stirring leaves, I realize all of these air-, water-, and earthborne creatures make a terrific din in a place where cars, trains, airplanes, barking dogs, or fighting neighbors don’t devour in great gulps the Earth’s quiet pauses between movements.

Birds are especially noisy, their wingbeats whistling, whumping, whispering, and generally registering audibly with every movement. Except for the owl, of course, whose wing structure and feathering make it into a silent stealth bomber. Even when birds like swifts aren’t beating the air with their wings, the way they slice the fabric of the wind frequently makes the same sound as a high velocity projectile zipping past, vrrrrr and vvving.

So three of the vultures pass by, not flapping now, but drifting so close in I can meet the eye of each that’s my side of the bird’s head. A trailing fourth bird comes along, and I happen to be looking its way when it rises suddenly from just above the ledge barely thirty feet out and at eye level. Immediately spotting me, it staggers momentarily in the air, surprised. It flaps its great wings two or three times to regain control. Those wingbeats sound exactly like the noise that drew my attention ’round to the previous three birds, so I think one or more of those three, coming upon me suddenly, similarly staggered in startlement. I’ve witnessed ravens exhibit the same behavior, stumbling mid-air on coming upon me unexpectedly and too close in for their comfort.

But vultures are, at their cores, unflappable. After that rustle of alarm, they regain composure and return to their drift, not batting a wing and apparently without altering their course by much. Off they all four go, sailing along the cliff faces, till on some signal they rise into the air and head west.

White-throated swifts zip around, as expected, filling the air with their laughing twitter, though it would of course be wrong to suppose they only sing for the sake of making noise. The white-throated swift incident I wrote of here suddenly, dramtically, and forever altered my consciousness of what birds are about . I’ve learned much since then, the chiefest thing being to pay closer attention. It hardly atones for my ignorance in that haunting incident, but I’m better for it.

Birds touch each other with song and through song keep in touch. In the case of swallows and maybe swifts, both of which on the wing are extremely chatty, I suspect some form of echo location at work. Both species hunt through the air for their food, snatching it on the wing, like bats. Watching swallows swirl in against a cliff, I noticed that at certain points in their singing they suddenly turn away from the stone, as if echoes of their flight notes bouncing off rock informed them better than their sight when to veer away.

Nothing I think might be is conclusive, of course. But sometimes, where understanding is to flourish, you must first prepare the gound with an abundance of imaginings.

In proximity to me waving its wind-stirred, blue-berried limbs stands a juniper in company with a hearty ephedra (Mormon tea) growing beneath one of its branches and in toward its trunk. At my left foot, in what must be only a shallow mound of wind-deposited soil that has collected in a stone basin, stands a very small— twenty-to-twenty-four inch tall— pinyon pine. Growing in tandem with this is a similarly dwarfen cliff rose. It would seem those two alone would strain the resources of the patch in which they grow, yet a third occupant lives close in to the pine’s roots, a claret cup cactus, forming a single reddish bud off one of its small, star-spined barrels.

For years, these three plants have grown in companionship together on their little soil island situated on a sea of stone. What do these three plants know of each other, living with their roots entangled as they must be?

I stand up to stretch my legs and walk to the other side of the cliff in time to witness a finch flutter straight up past the cliff singing a jazzy tune. It flips over in the air and flutters back down out of sight. As I return to my perch, I notice a large mammal crossing one of the beaver ponds about a quarter of a mile south of where I stand. I think it’s a deer but there’s something off about its movements. Hard to tell from here, but it appears to be limping heavily, and a drag in its walk suggests pain overall.

Budding cottonwood branches hide it for a moment, then it emerges to my sight, walking in that slow, suffering way across the old sandbar that has become a sage flat . Then it’s gone.

Looking more closely at those cottonwood trees, I notice they’re not budding in concert, or don’t appear to be. Why are some trees greening up way ahead of their kin? Next time I’m down there, I’ll pay closer attention.

The swifts have gone now, having moved on to other hunting grounds or responded to a different signal. I look up in time to witness a great blue heron parachute into the canyon, its huge wings arched to slow its descent. It glides down a slope of air toward the stream in perfect control then drops below bank level. Through breaks in the trees and where dips in the bank permit, I see it flapping its wings as it cruises along the stream seeking an advantageous landing spot.

High above, an eagle soars. I try to follow its flight, hoping it might come close by. But while I’m watching, it suddenly disappears. This talent eagles have for disappearing into the light amazes me. It seems they have nothing to hide them up there but thin air, yet they conjure themselves into it and appear out of it like sorcerers.

Time to go home and plant trees, a project we started last night but failed to complete. The kids and I worked all evening while the stars appeared, Orion twinkling out of the blue. We dug in our hard red soil, getting only three and a half of the six planting holes excavated. Tomorrow I hope we can go hike the Grand Gulch trail, as far as time permits, so we need to try to get the tree-planting task done today, if possible. Also up this week: starting my summer vegetables from seed: squash, melons, cucumbers, etc.

Later. The first hummingbird arrived at the feeders today, a male black-chinned. I was out on the back porch pushing my daughter Teah, whose birthday it also happens to be, in her wheelchair up and down the porch’s length when I heard the bird’s trill. My other daughter inside the house saw it through the window and came out quickly, eyes aglow. We both smiled broadly at each other, happy at the bird’s arrival. “Our hummingbird masters have returned,” I said. “Go mix up the sugar formula.” We’ll spend the next four plus months serving these demanding little creatures and reaping the profound rewards of their company. They start out shy, watching us carefully while they feed at the nectar cups, but eventually they’ll start accosting us whenever conditions don’t satisfy the precision of their natures. During the summer, we accomodate black-chinned, rufous, and broad-tailed hummingbirds, but the black-chinned birds are the most populous and social.

Soooo … dear reader, what did you do this fine Earth Day?

The day after Earth Day, more black-chinned hummingbirds arrive in the a.m., mostly mature males at first, wearing their black executioners’ hoods and opalescent violet throat-patch bandannas. Later in the afternoon what are probably immature males arrive. The younger males are plumaged much like the females, no hoods, no throat patches, head-to-bill variously toned grey feathers with not especially distinct markings, so often it’s hard to tell the difference. Their aggression around the feeders suggests male rather than female, but who knows. At least five visited today, and that provided enough players for the games to begin. Jousting, chasing, and aerial territorial display acrobatics lasted until just after sunset.

The hummingbirds definitely liven up the back porch environment. My special needs daughter, who for years disliked going outside because of the uncertain nature of the ulterior environment, has lately developed a ravenous appetite for outdoor adventure. For her, deeds of derring do amount to traveling in her wheelchair up and down the porch, built to the second story (main floor) door, and gulping the wind that blows and gushes across the porch. Also, she can hear the neighs, baas, clucks and barks, moos of neighbors’ animals. Both Sunday and last night we were out there around midnight, when a bold-tongued coyote on nearby neighbors’ properties berated the local dogs. Down in dens the parents have excavated, coyote pups are being born now, so maybe the animal’s especially brazen behavior had some relationship to that blessed event.

Since these wheelchair spins are one of M’s highest— indeed, nearly her only— excitement, I spend anywhere from two-and-a-half to three hours a day out there as her wheelchair chauffeur. This job has its charms, it puts me at the scene of action I wouldn’t witness otherwise. For instance, three evenings ago I was chauffeuring M just before sunset when I reached the east end of the porch in time to see four Canadian geese flying in a vee due west into the sun, low down, directly over the porch. I was able to observe the steadiness of their bodies between their wings and the leader flying at the top of the vee turn its head slightly to the southwest, as if appraising options, as would be its responsibility. The amber tones of the setting sun raised detail in the birds’ wings, bills, and bodies and I could see the setting sun glinting in some of the birds’ eyes. It was a photo op, and me without a camera.

Shortly after the geese flew over, a turkey vulture reeled through, and moments after that, a cluster of cliff swallows tumbled all over the air above the back yard and veered around the house to the fields out front.

To such right-place-at-the-right-time moments I can now add the hummingbirds, who fill in the gaps between ravens tripping the light fantastic in tight pairs and other passing details of desert life. Plus of all the birds, the hummers come in the closest, flying up to the feeders while I’m pushing M past. As I said, they’re shy now, but that’s melting fast in the heat of duels raging above nectar cups and my frequent, non-threatening presence. Some of these birds are definitely returns. It isn’t that I can tell individual birds apart, it’s that the behavior of some of the recent arrivals shows they know the ropes. Black-chins are the most human tolerant of the types of hummers that visit our feeders. I depend upon their company in the summer as much as I depend upon my garden to provide.

In a week or so, their numbers will multiply, and we’ll have maybe twenty-four birds buzzing the feeders, especially just before they turn in for the night. When the local nectarous flowers open in abundance a few weeks later, some of the hummers will disperse to the desert. Maybe half will return for a nighcap just before nightfall, but generally, their numbers at the porch will drop off.

Also, after having to change location plans, we managed to get three of our six new trees planted this evening, once more as the stars turned out— both of the nectarines and one of the cherries. One more cherry will go out back, then we’ll set the two apricots in the front yard.

Approximately fifty-six of my tomato seedlings erupted, we’ll see how it goes this year. Last year was terrible, tomato-wise. A cold spring and cooler-than-usual summer put the tomatoes off. We hardly got anything, although I was extremely pleased with how beautiful and hardy the Seed Savers’ Cherokee purple strain turned out to be. If all goes well this year, I’m saving seeds from that strain. I’ve never seen more beautiful Cherokee purples. Nature’s— and seed savers’— works of art. Also growing this year: brandywines (also a Seed Saver’s strain), striped Germans, green zebras, and one Old Flame made it from nine cells wherein I planted very old seed. If I manage to nurture that plant to the point of establishing it in the garden, then one or two tomatoes from it will provide enough seed to increase my seed stock.

I’ve had good success producing and saving seed from a scarlet runner bean my neighbor gave me a few seeds for a couple years back. She thought they were Anasazi beans. I look forward to increasing that seed stock this year. Anyone wanting scarlet runner beans, which attract hummingbirds, I might have some seeds at the end of the harvest I can send.

Ya know, life’s a garden.

LikeLike

This Earth Day I took a small paintbox with me up onto the bench trail by Provo.

This was, I think, the warmest day yet this spring. Small cumulus clouds were scattered above most of the mountain ridges. The clouds would bubble up as if on low boil, but then dissipate before becoming very large. Far to the north and west, visible beyond several mountain ranges, storm clouds lined the horizon.

The scrub oak are still without leaves, and have a purple-grey cast to them. The leaves they dropped last year give their tangled trunks and branches an umber under layer. Along the trail’s edges and on the lower slopes, the surprising green of new grass is pushing past the tawny-grey winter kill.

There was surprisingly little wildlife there that day. While I painted, a few unidentified birds would occasionally flit by. Some butterflies fluttered by. Off in the distance, three large raptors, probably vultures, soared over Orem. I usually see more wildlife on this trail, in spite of the noise that washes up the mountainside from the town below.

I didn’t see any “real” eagles this day.

While I was painting, a couple of gnats became stuck to my canvas panel. When this sort of thing happens, it’s usually more trouble to try and remove the hapless bugs from the wet paint, than it is to remove them later when the paint is dry. Sometimes the bugs can’t be removed. If you visit any exhibit where the paintings were done “en plein air”, and look closely at the pictures, you will probably find small bugs stuck to some of them. In plein air circles, when bugs become stuck to a painting, especially in the sky portion, they are called “eagles.”

Really.

LikeLike

Now I’ll be looking for the “eagles” in landscapes.

Interesting that in the plein air craft, bits of the landscape might become part of the painting of the landscape from which they came.

I sometimes get grit in my hiking journal, but that’s easily blown off.

LikeLike

Ah, tomato time.

Over the years, I’ve decided I’m too impatient for Brandywines. A hundred and ten days is beyond my time horizon. Drool-inducing though they may be.

Fifty-six starts? Will you plant all that make it to adolescence?

LikeLike

I know tricks for moving tomato maturity along more quickly. One obvious one: use black fabric weed barrier to warm the soil above the plants’ roots.

A favorite trick that won’t work where I live now because our property’s in a wind tunnel:

Using the tomato cages placed around the plants as support, throw a sheet of drop-cloth type heavy-gauge clear plastic (like that used to protect furniture when you’re painting a room) over the plants the day you plant them. Fix the plastic in place. I clothespin the sheet to the top rims of the cages where it makes sense to do so. The sheet of plastic needs to be broad enough to touch the ground with material to spare. Anchor that plastic on two ends using whatever works. I set rocks, pieces of lumber, etc. on the ends. On the top of the plastic where it forms the roof of this el-cheapo greenhouse, puncture the plastic in low spots to allow for the drainage of rainwater.

The tricky parts: in the heat of the day, you have to roll up the “front” and “back” of the plastic to allow for airflow through the greenhouse. If you don’t, the plants cook. At night, you drop those roll-ups to keep warmth in. Also, when the plants reach the point where they grow so far past the top of the cages that the plastic might damage them, you should remove the greenhouse altogether.

If the plants get a lot of blossoms before they reach that point, on very warm days, remove the greenhouse so the bumblebees can get to the flowers. Tomatoes are to a degree self-pollinating, but every little bit helps.

Easier, of course, to just bolster your tomato strategy with early-ripening varieties. But I haven’t found an early variety heirloom yet that I’m happy with. The green zebras listed above and the Cherokee purples ripen earlier than the brandys but not as early as the early girl hybrids.

Fifty-six starts? Will you plant all that make it to adolescence?

I can easily make use of the fruit of fifty-six plants, even in a good year. What a carrot is to you, greenfrog, a tomato is to me: a lens through which I see the world and the world sees me. 😉

But if all goes well I may give away plants to interested parties. Can’t have too many heirloom tomato fans. Biodiversity, and all that.

(Invisolink Easter egg above.)

LikeLike

Patricia, I’m very pleased to find this blog. I have a great interest in literary science and nature writing. At this point I’m reading it (Barry Lopez, Wendell Berry), but want to try my hand at it. I’ve been reading through some of the posts on this blog and find them to be good examples for me as well as being interesting in their own right.

Thanks for starting this. I love the looks of it, too!

LikeLike

Thank you, Mary A, for finding WIZ! You’re most welcome here.

Enjoy, and please feel free to participate when you feel the urge.

BTW, how did you find this blog?

LikeLike

Patricia, I was poking around on A Motley Vision after not reading blogs for a while when I saw the piece introducing WIZ. I put my writing blog as my website when I commented, but I also have an LDS blog called By Study and Also By Faith (and a political/miscellanceous blog called Scholar).

I would like to submit something here after I’ve done a little more nature/science writing to develop my skills.

I saw a poem and some comments by greenfrog. I don’t know if he’ll remember, but I used to participate in the forums at Nauvoo and posted there as Tyro. So, greenfrog, hi!

Mary

LikeLike

Hi Mary. It’s been a long time since my Nauvoo days. Glad to see you here.

P,

Carrots, of course the more the merrier. Tomatoes? I plant about a dozen and until the end of August, my diet shifts to red (and yellow and orange and stripey and purple) and with a bottle of olive oil and a salt shaker, I can eat just about all they produce. Sometimes I do them up in quarters, season them, and dump cottage cheese on to meet protein requirements. When August wanes, we shift to homemade tomato soup, which can use the four or five pounds per day we get from our dozen vines.

I imagine that with 56 plants, we’d either have to make more friends or start bottling.

Admittedly, neither seems like a bad idea.

s

LikeLike

Once the plants are heavy, I go salsa. Days at a time.

And it looks like it’s time for a garden post.

LikeLike

I was poking around on A Motley Vision after not reading blogs for a while when I saw the piece introducing WIZ.

Mary A, sounds like you have some experiences turning over and looking under rocks.

The Field Notes posts on this site exist for people to try out nature writing, see how it feels on them. They’re kind of like nature writers’ campfire rings for show-and-tell. Pull up a rock (after turning it over to see what’s underneath).

Also, sure, when you feel ready, let’s see what you’ve got.

LikeLike